The Warble

The Official Blog of Karen Ullo

News! News! News…letter

Hello Everybody out there in Blog Land,

I just wanted to take a minute to let you know that I’ve finally joined the Internet Age and created an email newsletter. If you want to receive all my latest writing news, blog posts, recipes, and more, hand-curated and wrapped up in a tidy package delivered right to your inbox, you can sign up here.

I tried to embed the signup form on this page for you, but of course, code and I don’t get along, even when real programmers write it. It can smell the fear exuding from my every pore. But the newsletter will still be awesome!

Love, your friendly neighborhood technophobe,

Karen

Karen Ullo is a writer, musician, wife, and mother of two small tornadoes–er, boys. Her novels are Jennifer the Damned (2015) and Cinder Allia (coming in 2017.) She is also a regular Meatless Friday chef for Catholicmom.com. Find out more at www.karenullo.com.

Stammering

I’m preparing to attend a conference at Notre Dame in just a few weeks called Trying to Say God: Re-enchanting Catholic Literature. I’m terribly excited to finally meet face to face many of the movers and shakers of the Catholic literary world. It’s an honor and an opportunity for which I’m deeply grateful. However, the conference organizers recently sent a list of essays as preparatory reading—many of which I had read before, and which I’m sure many of you will recognize—and I noticed something that disturbed me. All of these essays deal directly or tangentially with the perceived dearth of a Catholic literary culture in our current age. They are:

Dana Gioia, “The Catholic Writer Today,” Dec. 2013, First Things

Paul Elie, “Has Fiction Lost its Faith?” New York Times, Dec. 19, 2012

Kaya Oakes, “Writers Blocked: The State of Catholic Writing Today,” America, April 28, 2014

Randy Boyagoda, “Faith in Fiction,” First Things, August 2013

Francis Spufford, “Spiritual Literature for Atheists,” First Things, November 2015

David Griffith, “The Problem with Waiting” Image – Good Letters

There’s an awful lot of good stuff here, many very salient points and much healthy debate written by people far more learned in these matters than I. I am grateful to all of them for their contributions to this very necessary conversation, and I agree with at least portions of every essay. However, in (re)reading this list in close succession, I could not help but be overwhelmed by the distinct lack of emphasis on what ought to be a Christian’s first and only goal: to do the will of God. Just to make sure I was paying attention, I went back and ran a search through each of these essays for the following words: vocation, discern, pray, love, humility. Some of them never appear; a few appear in passing, as in the titles of quoted works, or in a very general sense. For example, Gioia says of the past literary “golden age”: “Catholicism was not only seen as a worldview consistent with a literary or artistic vocation… the Roman Church was often regarded as the faith most compatible with the artistic temperament.” It’s the only time he mentions vocation. The author who comes closest to proposing prayer and humility as solutions to the problem of the Catholic literary culture is Spufford:

Wild justice—justice unmediated and unfiltered—is different from the thing we painstakingly try to make in courtrooms. Wild charity—love unmixed and uncompromised—is fearfully unlike the adulterated product we are used to. It is a terrible thing to fall into the hands of the living God.

That’s it. Six essays about how to create a Catholic literary renewal, and only one mention of “love unmixed and uncompromised.”

Maybe this is our real problem. The focus of anything we build in the name of Christ and His Church ought never to be on the product or the people who build it, but on the One who works through us and through our works.

I am the least and the lowest among Catholic writers. My résumé looks like a post-it note next to those of the authors above. But I dare to say: the solution to whatever lack of Catholic literature there may be lies not in changing the attitudes of publishing houses and periodicals, nor the outlook of universities and academics, nor in establishing our own periodicals and publishing houses, nor in the coming of some great literary genius to inspire and renew the languid modern imagination—though it is not wrong to seek any of these things. But to speak about such practicalities without speaking about the proper spiritual context in which to pursue these goals is to put the cart before the horse. The real answer to our literary woes lies in the same place where the answer to a spiritual problem always lies: in prayer, trust, humility, and the action of God’s Holy Spirit. Pope St. John Paul II wrote in his Letter to Artists:

The particular vocation of individual artists decides the arena in which they serve and points as well to the tasks they must assume, the hard work they must endure and the responsibility they must accept. Artists who are conscious of all this know too that they must labour without allowing themselves to be driven by the search for empty glory or the craving for cheap popularity, and still less by the calculation of some possible profit for themselves. There is therefore an ethic, even a “spirituality” of artistic service, which contributes in its way to the life and renewal of a people.

I do not doubt for an instant that the authors of all six essays are prayerful people who have devoted themselves to this “spirituality of artistic service.” But are we—even as Catholics speaking mostly to an audience of other Catholics—afraid to say that Christ is the Way to our literary, as well as our actual, salvation? Are we afraid to forego the language of the academic essay in order to address our own spiritual sickness? If we cannot “say God” even in our appraisals of our own Catholic culture, how do we propose to do it in our poetry, our fiction, our memoirs? God, who has the words of everlasting life, has no need of a Catholic literary culture; if one exists, it is only by His gracious will. If you and I desire such a thing, then let’s get down on our knees and beg for it with humility and hearts that are open to God’s will. Perhaps if we seek first the kingdom, then all these things shall be added to us besides.

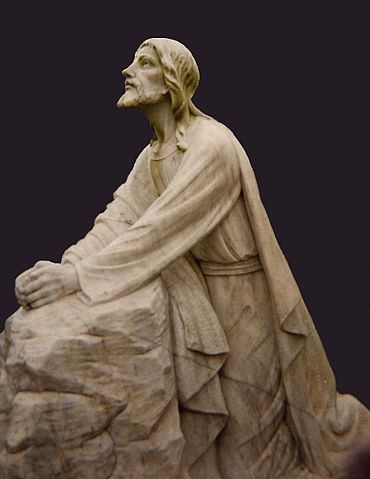

All artists experience the unbridgeable gap which lies between the work of their hands, however successful it may be, and the dazzling perfection of the beauty glimpsed in the ardour of the creative moment: what they manage to express in their painting, their sculpting, their creating is no more than a glimmer of the splendour which flared for a moment before the eyes of their spirit. Believers find nothing strange in this: they know that they have had a momentary glimpse of the abyss of light which has its original wellspring in God. Is it in any way surprising that this leaves the spirit overwhelmed as it were, so that it can only stammer in reply? (John Paul II, Letter to Artists)

Christian artists are called to gaze in awe at the splendour of our Creator, who spoke us into being. Only then, and only if He grants us the vocation to do so, do we humbly go forth and stammer.

The Overrated Art of the Opening Line

Anyone who has ever taken a creative writing class has been indoctrinated with the importance of the first impression. That elusive perfect opening image, the one that instantly hooks the reader, that declares this book to be un-put-down-able, has developed an almost mythical importance among fiction writers. My Google search for “how to write a great opening line” turned up 83.5 million results. There are even first line generators to get you started, if you happen to be incapable of forming a sentence but still want to be a writer. However, it recently occurred to me that I could not recite the opening line from a single one of my favorite novels. The ones that I’ve included here, I had to go look up. On top of that, my all-time favorite opening line is not really an opening line at all.

Something here is fishy.

My all-time favorite opening line is from Slaughterhouse-Five. It says, “Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.” It does everything a great opening line should do: it establishes an unmistakable authorial tone, which even dares to break the “fourth wall” and speak directly to the reader; it introduces a character whose very name, “Billy Pilgrim,” sets him up as an everyman on a journey; and it creates a circumstance that makes Billy Pilgrim ridiculously interesting, namely that he’s come unstuck in time—whatever that means, but I sure want to read the book to find out. It’s eight words of perfectly-written dramatic hook.

But it’s not the opening line. It’s the beginning of chapter two . . . and it also appears at the end of chapter one:

I’ve finished my war book now. The next one I write is going to be fun.

This one is a failure, and it had to be, since it was written by a pillar of salt. It begins like this:

Listen:

Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.

It ends like this:

Poo-tee-weet?

“Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time” is a spectacularly brilliant opening line that gets intentionally buried, and whose impact is intentionally undercut by stating it before its proper dramatic time. It’s almost like Kurt Vonnegut took the rule book for writing opening lines, dared anyone to do it better, and then threw the story in a trash can like Kilgore Trout was sometimes wont to do.

The actual opening line of Slaughterhouse-Five says, “All this happened, more or less.” Which is complete and utter nonsense, and provides no dramatic hook at all.

And so it goes.

But, of course, there are plenty of more famous opening lines than my particular favorite. Perhaps the one that is most frequently mentioned when people say “Famous Opening Lines” is from Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Enough with the comma splices already.

Punctuation aside, there is not a single element of drama developed in this rambling paragraph of a sentence. Not a single character is introduced; we have no idea what time period is actually being described by all these superlatives; and the only active verb contained within the string of passives is “insisted,” which carries all the dramatic weight of a toddler stamping his foot.

And yet, it’s arguably the most famous opening line ever written.

My favorite book of recent times is The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. The opening line says: “Here is a small fact: You are going to die.” Which isn’t drama, and it isn’t news.

Another, even more recent book that I very much enjoyed is The Orphan Mother by Robert Hicks. It begins:

December 12, 1912

To the shabby house on Columbia Avenue they came, the four of them, all in black, narrow ties fastened with jeweled stickpins about their necks.

At least something happens in this one: the drama of the jeweled stickpin. How riveting.

Here are a few particularly dull opening lines that I found on the American Book Review list of 100 Best First Lines from Novels:

Mother died today. —Albert Camus, The Stranger

Where now? Who now? When now? —Samuel Beckett, The Unnamable

For a long time, I went to bed early. —Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way

He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish. —Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea

Elmer Gantry was drunk. —Sinclair Lewis, Elmer Gantry

You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a winter’s night a traveler. —Italo Calvino, If on a winter’s night a traveler

If I wrote “You are about to begin reading Karen Ullo’s new novel, [insert title here]” and turned it in to my creative writing professor in any university in the world, it would be handed back to me covered in bright red ink. Yet there it is, on the list of the top 100 first lines ever written. It’s not a great line. It’s not even a good line.

But it’s a wonderful book.

What makes a great opening line is never the line itself. Certainly, it’s possible to put a zinger right up front, to entrap the reader Billy Pilgrim-style and—if you can manage it—never let him go. But what really makes a great opening line is the appreciation that comes from having savored the whole novel. The opening line is only truly beautiful after you have taken the entire journey with the characters, and then you stop to look back across the trodden path to see where you started and how far you’ve come. My, what a distance lies between “All this happened, more or less” and “Poo-tee-weet?”. “Here is a small fact: You are going to die” means quite a bit more once you know that Death himself is speaking. “You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a winter’s night a traveler,” is really the only appropriate way to begin a book that . . . does whatever it is that book actually does. Just go read it.

I sympathize with every teacher or editor who has ever had to try to convince an aspiring writer that “[Character name] was drunk” is a terribly insipid way to try to catch a reader’s attention. I have had my fair share of those conversations; but the aspiring writer does have Sinclair Lewis on his side. The truth is, the art of the opening line has nothing whatsoever to do with an exciting, dramatic hook, or even clever wording; the only way to make an opening line “great” is to follow it with a magnificent story. Dickens’s comma splices hold such an exalted place in literature because they are the gateway to “a far, far better thing” than one line could ever hold.

Karen Ullo is a writer, musician, wife, and mother of two small tornadoes–er, boys. Her novels are Jennifer the Damned (2015) and Cinder Allia (coming in 2017.) She is also a regular Meatless Friday chef for Catholicmom.com. Find out more at www.karenullo.com.

Cinder Allia coming soon!

I’m thrilled to announce that my second novel, Cinder Allia, will be coming your way this summer! Dates are still tentative, but the gears are turning to get it out to you, hopefully in time for you to bring it to the beach! Here’s a hint of things to come:

Cinder Allia has spent eight years living under her stepmother’s brutal thumb, wrongly punished for having caused her mother’s death. She lives for the day when the prince will grant her justice; but her fairy godmother shatters her hope with the news that the prince has died in battle. Allia escapes in search of her own happy ending, but her journey draws her into the turbulent waters of war and politics in a kingdom where the prince’s death has left chaos and division.

Cinder Allia turns a traditional fairy tale upside down and weaves it into an epic filled with espionage, treason, magic, and romance. What happens when the damsel in distress must save not only herself, but her kingdom? What price is she willing to pay for justice? And can a woman who has lost her prince ever find true love?

Surrounded by a cast that includes gallant knights, turncoat revolutionaries, a crippled prince who lives in hiding, a priest who is also a spy, and the man whose love Allia longs for most—her father—Cinder Allia is an unforgettable story about hope, courage, and the healing power of pain.

Karen Ullo is a writer, musician, wife, and mother of two small tornadoes—er, boys. Her novels are Jennifer the Damned (2015) and Cinder Allia (coming in 2017.) To find out more, go to www.karenullo.com.

Recent Comments