I’m preparing to attend a conference at Notre Dame in just a few weeks called Trying to Say God: Re-enchanting Catholic Literature. I’m terribly excited to finally meet face to face many of the movers and shakers of the Catholic literary world. It’s an honor and an opportunity for which I’m deeply grateful. However, the conference organizers recently sent a list of essays as preparatory reading—many of which I had read before, and which I’m sure many of you will recognize—and I noticed something that disturbed me. All of these essays deal directly or tangentially with the perceived dearth of a Catholic literary culture in our current age. They are:

Dana Gioia, “The Catholic Writer Today,” Dec. 2013, First Things

Paul Elie, “Has Fiction Lost its Faith?” New York Times, Dec. 19, 2012

Kaya Oakes, “Writers Blocked: The State of Catholic Writing Today,” America, April 28, 2014

Randy Boyagoda, “Faith in Fiction,” First Things, August 2013

Francis Spufford, “Spiritual Literature for Atheists,” First Things, November 2015

David Griffith, “The Problem with Waiting” Image – Good Letters

There’s an awful lot of good stuff here, many very salient points and much healthy debate written by people far more learned in these matters than I. I am grateful to all of them for their contributions to this very necessary conversation, and I agree with at least portions of every essay. However, in (re)reading this list in close succession, I could not help but be overwhelmed by the distinct lack of emphasis on what ought to be a Christian’s first and only goal: to do the will of God. Just to make sure I was paying attention, I went back and ran a search through each of these essays for the following words: vocation, discern, pray, love, humility. Some of them never appear; a few appear in passing, as in the titles of quoted works, or in a very general sense. For example, Gioia says of the past literary “golden age”: “Catholicism was not only seen as a worldview consistent with a literary or artistic vocation… the Roman Church was often regarded as the faith most compatible with the artistic temperament.” It’s the only time he mentions vocation. The author who comes closest to proposing prayer and humility as solutions to the problem of the Catholic literary culture is Spufford:

Wild justice—justice unmediated and unfiltered—is different from the thing we painstakingly try to make in courtrooms. Wild charity—love unmixed and uncompromised—is fearfully unlike the adulterated product we are used to. It is a terrible thing to fall into the hands of the living God.

That’s it. Six essays about how to create a Catholic literary renewal, and only one mention of “love unmixed and uncompromised.”

Maybe this is our real problem. The focus of anything we build in the name of Christ and His Church ought never to be on the product or the people who build it, but on the One who works through us and through our works.

I am the least and the lowest among Catholic writers. My résumé looks like a post-it note next to those of the authors above. But I dare to say: the solution to whatever lack of Catholic literature there may be lies not in changing the attitudes of publishing houses and periodicals, nor the outlook of universities and academics, nor in establishing our own periodicals and publishing houses, nor in the coming of some great literary genius to inspire and renew the languid modern imagination—though it is not wrong to seek any of these things. But to speak about such practicalities without speaking about the proper spiritual context in which to pursue these goals is to put the cart before the horse. The real answer to our literary woes lies in the same place where the answer to a spiritual problem always lies: in prayer, trust, humility, and the action of God’s Holy Spirit. Pope St. John Paul II wrote in his Letter to Artists:

The particular vocation of individual artists decides the arena in which they serve and points as well to the tasks they must assume, the hard work they must endure and the responsibility they must accept. Artists who are conscious of all this know too that they must labour without allowing themselves to be driven by the search for empty glory or the craving for cheap popularity, and still less by the calculation of some possible profit for themselves. There is therefore an ethic, even a “spirituality” of artistic service, which contributes in its way to the life and renewal of a people.

I do not doubt for an instant that the authors of all six essays are prayerful people who have devoted themselves to this “spirituality of artistic service.” But are we—even as Catholics speaking mostly to an audience of other Catholics—afraid to say that Christ is the Way to our literary, as well as our actual, salvation? Are we afraid to forego the language of the academic essay in order to address our own spiritual sickness? If we cannot “say God” even in our appraisals of our own Catholic culture, how do we propose to do it in our poetry, our fiction, our memoirs? God, who has the words of everlasting life, has no need of a Catholic literary culture; if one exists, it is only by His gracious will. If you and I desire such a thing, then let’s get down on our knees and beg for it with humility and hearts that are open to God’s will. Perhaps if we seek first the kingdom, then all these things shall be added to us besides.

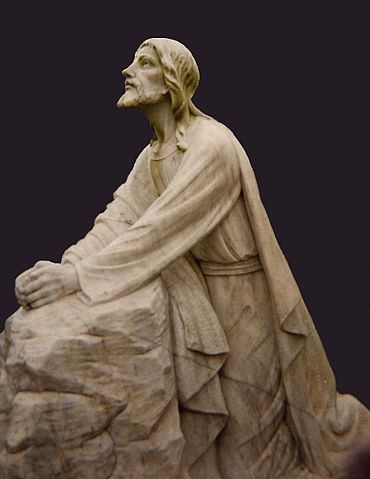

All artists experience the unbridgeable gap which lies between the work of their hands, however successful it may be, and the dazzling perfection of the beauty glimpsed in the ardour of the creative moment: what they manage to express in their painting, their sculpting, their creating is no more than a glimmer of the splendour which flared for a moment before the eyes of their spirit. Believers find nothing strange in this: they know that they have had a momentary glimpse of the abyss of light which has its original wellspring in God. Is it in any way surprising that this leaves the spirit overwhelmed as it were, so that it can only stammer in reply? (John Paul II, Letter to Artists)

Christian artists are called to gaze in awe at the splendour of our Creator, who spoke us into being. Only then, and only if He grants us the vocation to do so, do we humbly go forth and stammer.

Recent Comments