The Warble

The Official Blog of Karen Ullo

Adventures in Music-ing

“To music” really ought to be a verb. I realize the -ing form of it would look rather awful: you’d either have to make it musicking—which looks sickly—or you’d have to run the risk of musicing being pronounced like “muse icing”—which is an interesting image, but not exactly what I’m going for. Still, there really is more to music-ing than “making” music. The usual phrase connotes that music is a thing, like a table or a statue. But music is not a form of matter; it’s a form of energy. Music only exists when it is in motion. A vinyl record or a CD might be called “potential music,” but you’ve got to spin it for it to play. The potential energy of the hammers in a piano must become kinetic, and the kinetic energy must be converted to sound waves, or the strings will remain forever silent. Music is always active; inertia must be overcome by force not once for all time, like the energy channeled into a sculptor’s chisel, but over and over again, at the very moment when the music is required, or else it will not exist. Music-ing is always a verb.

Bells like these

I’ve been the music director at a Catholic parish for almost thirteen years now, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned for sure, it is that Murphy’s Law applies double to music, especially during Christmas and Easter. Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong. On my very first Christmas Eve in my current job, the vigil Masses ran smoothly, including a children’s “hand bell” performance using the color-coded bells popular in preschools and kindergartens. (Our organist owns the company that markets those bells, and she records the accompaniment tracks herself.) But later, when we arrived for midnight Mass, the organ would not play. At all. It wasn’t until Christmas morning that the pastor figured out some of the kids from the bell choir had banged on the back of the organ console and dislodged the fuses.

This liturgical year in particular has been a comedy of holiday errors. Once again, the Christmas Eve vigil Masses ran smoothly, but when I set up all the microphones for midnight Mass, I flipped on the sound system and. . . BUZZ. Not feedback. Just something-ain’t-right noise. Do you know how long the process of elimination takes to figure out what’s wrong with a sound system? It could be any single microphone, cable, or sound board channel causing the problem, and in order to test them, I had to keep turning the system on and off. And the switch is in the sacristy, a good thirty yards or so from where the musicians set up. And I was barely six weeks recovered from foot surgery, hobbling back and forth across that distance, until I stationed the deacon at the switch and kept signaling to him across the church. But it turned out to be a good thing we had an excuse not to perform our prelude music, because—despite setting an alarm—the pianist overslept. While I was desperately troubleshooting the sound system, the organist had to call and wake her up. The pianist is normally very responsible and punctual, but this time she had to stumble into church half-way through the gathering hymn, right after I finally ditched the offending microphone, without having time to determine whether it was the cable or the mic itself causing the buzz.

Music-ing. Gotta love it.

Still, no matter how many things go wrong, in my almost thirteen years as music director, we have never had a complete musical meltdown. We’ve had plenty of less-than-perfect services, but, no matter how close we’ve come, we have never had to simply throw in the towel and say, “Sorry, folks, no music today.” Much of this, of course, has to do with careful planning and built-in redundancy. I mentioned both an organist and a pianist; at most Masses, we use both instruments at the same time, which also means that if one accompanist gets sick or goes on vacation, the other is there to cover. If the organ malfunctions, we still have the piano. If the pianist oversleeps, we still have the organ. If I can’t sing, the pianist can cantor, too. But an even bigger part of our record of no meltdowns is the fact that we have had plenty of heavenly intervention.

The most obvious example of this came a few years ago on a Sunday during Lent. Because of a perfect storm of personal emergencies, both of our accompanists had to be out at the same time. Although I’d made plenty of calls, I couldn’t find a sub. I arrived at church on Sunday morning having prepared the choir for an all-a cappella service, and I announced our plan to the congregation before Mass. No sooner had I finished the announcement than a man I had never met appeared at my elbow and said, “You need a piano player?” I looked at him in shock and said, “Can you really do it on this short of notice?” He more or less grunted, “Yes.” I thought to myself, the worst thing that happens is we have one terrible hymn and then I tell him, “Thanks, but no thanks.” So I set the sheet music in front of him… and he blew us all out of the water. It turned out he was the band director from the local Catholic high school, someone I had emailed and spoken to on the phone but never met in person. People call him “Doc” because he’s got a Ph.D. in music.

The pastor’s reaction after Mass: “Angel of God, my guardian dear…”

However, the heavenly intervention usually comes in ways that are much less obvious to the people sitting in the pews. More often, it comes as grace in the midst of personal suffering. This year’s Holy Week was probably the most extreme example our musicians had ever witnessed. Holy Week has a tendency to be a great physical trial for me personally. There was the year when I premiered my original setting of the Exsultet with chronic tonsillitis. There was the year when I caught a stomach bug on Wednesday, missed our final rehearsal, and barely managed to keep my drugged, dehydrated body upright to conduct Holy Thursday and Good Friday. But this year, I had major internal surgery less than a month before Easter. The things that still hurt the most for me to do post-op are singing and conducting. Add to that the fact that the pianist is fighting a problem with her wrist, one of our cantors got sick, and several choir members are in the middle of moving back into their renovated homes after the flood. Best of all, the organ developed a cipher ten minutes before the Easter Vigil. That means a particular note plays constantly even when no one presses the key.

This really should have been the year when we threw in the towel.

But of course, we didn’t. There was quite a lot of codeine involved in my performance this year, but somehow I was still alive and conscious—and on pitch!—at the end of the last Mass on Easter Sunday morning. Somehow, the pianist still played. Somehow, the exhausted choir full of flood victims still sang. Somehow, the organist even managed to negotiate the cipher. Despite the best efforts of the world to drown us out, Easter in our parish was still filled with beautiful music.

If that’s not the work of the Holy Spirit, I don’t know what is.

My history with music-ing is long, complicated, and filled with almost as much pain as love. I guess that’s how you know when you’ve got a vocation. No matter how I try to get around it, music-ing continues to be an adventure, even when I’m long past the point when I’d prefer it to be dull. But I suppose that, as with most things in life, if music-ing were not my own personal Passion, I’d be tempted to overlook the ways in which it is a continual source of grace.

Happy Easter!

Karen Ullo is the author of the novel Jennifer the Damned. To find out more, go to www.karenullo.com.

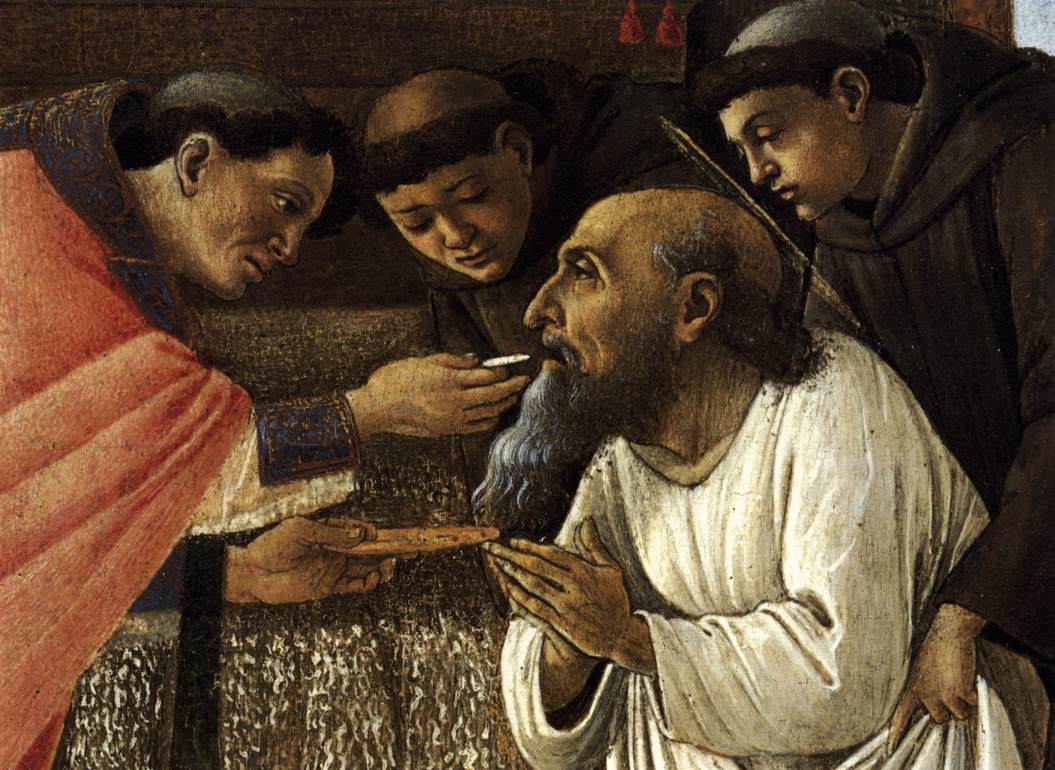

Easter Communion

Sandro Botticelli, The Last Communion of St. Jerome

Easter Communion by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Pure fasted faces draw unto this feast:

God comes all sweetness to your Lenten lips.

You striped in secret with breath-taking whips,

Those crooked rough-scored chequers may be pieced

To crosses meant for Jesu’s; you whom the East

With draught of thin and pursuant cold so nips

Breathe Easter now; you serged fellowships,

You vigil-keepers with low flames decreased,

God shall o’er-brim the measures you have spent

With oil of gladness, for sackcloth and frieze

And the ever-fretting shirt of punishment

Give myrrhy-threaded golden folds of ease.

Your scarce-sheathed bones are weary of being bent:

Lo, God shall strengthen all the feeble knees.

Karen Ullo is the author of the novel Jennifer the Damned. To find out more, go to www.karenullo.com.

The St. Joseph Altar—or, learning to love the culture you married into

I have a confession to make: I’ve been Catholic all my life, and I had never heard of a St. Joseph Altar until about ten years ago, when I married a man of Sicilian descent. He’s as much an American from South Louisiana as I am, but my cultural heritage is French, while he’s a Ullo from a town called Marrero. The number of vowels in those two words ought to tell you that his grandparents often seasoned vats of homemade tomato sauce with Italian prayers and buried statues of St. Joseph upside down when they wanted to sell a house—another tradition this Cajun girl had never heard of until I married into the tribe. I didn’t even know St. Joseph was the patron of Sicily, much less any of the finer points of the devotion.

Since my husband first started hounding me, the first March after we were married, to find a St. Joseph Altar to attend, it seems like suddenly they’re everywhere: articles popped up in the local Catholic newspaper, my parish school decided to host one, friends galore—even my own parents, who never took any interest in such things when I was growing up—often invite me to attend them. Apparently, the custom has deep roots in Louisiana, as it does almost anywhere in the U.S where there’s a large group of Sicilian immigrants. I’m just late to the party.

The tradition of the St. Joseph Altar dates back to the Middle Ages, when Sicily was suffering from drought and famine. The people prayed to St. Joseph to send rain to make their crops grow, but for a long time, the only thing that would grow—the crop that kept them alive—was the humble fava bean. When the rains finally came and the people harvested their crops, they set up an altar filled with the produce, gave thanks to St. Joseph, and then distributed the food to the poor. Since then, the annual altars, held on or near the Feast of St. Joseph on March 19, have become ever more elaborate, layered with symbol and ritual. You can read more about the history of the practice here and here.

The tradition of the St. Joseph Altar dates back to the Middle Ages, when Sicily was suffering from drought and famine. The people prayed to St. Joseph to send rain to make their crops grow, but for a long time, the only thing that would grow—the crop that kept them alive—was the humble fava bean. When the rains finally came and the people harvested their crops, they set up an altar filled with the produce, gave thanks to St. Joseph, and then distributed the food to the poor. Since then, the annual altars, held on or near the Feast of St. Joseph on March 19, have become ever more elaborate, layered with symbol and ritual. You can read more about the history of the practice here and here.

Much like St. Patrick’s Day for the Irish, St. Joseph’s Day appears to this outside observer to be more or less an excuse to throw a party during Lent. It’s a holy, philanthropic party, and it’s soberer than St. Paddy’s Day with its green beer, but it’s a party nonetheless. At the large, public altars I’ve attended, the food displayed on the altar itself will be given to the poor at the end of the day, but there is also a meal prepared to give away to anyone who comes, usually pasta with tomato sauce (of course!) and a boiled egg. There is no meat at a St. Joseph Altar because the feast falls during Lent, when Catholics historically ate no meat at all. The food is often sprinkled with bread crumbs to represent the sawdust of St. Joseph the carpenter (although at the altar we attended last Sunday, it wasn’t. This made my husband upset enough to ask if he could volunteer to help next year. I suspect he will be the official Bread Crumb Sprinkler.) Once you’ve finished your pasta and whatever vegetarian side dishes come with it, there are enough Italian sweets for every person there to rot three sets of teeth. I don’t know the names of most of them, and I couldn’t spell them if I did, but I am perfectly happy to be ignorant and just eat. As my own people would say, Mais, ça c’est bon!

After you have stuffed yourself and viewed the beautiful culinary artwork that adorns the altar—and tried desperately, if not quite successfully, to keep your children’s snatching fingers out of all that meticulously worked icing—the generous hosts send you home with a little paper baggie full of yet more cookies, a blessed fava bean, a small hunk of blessed bread, and—if your fervently Sicilian husband goes and asks for it—also little baggies of blessed salt. This is the part of the St. Joseph Altar that I’m having trouble learning to love, because I am not allowed to divest myself of any of these blessed objects, ever. According to my husband, the bread is meant to protect against natural disasters and the beans are good luck. Once, I threw away one of the hunks of bread because I cleaned out our cabinets and thought it was just a random, forgotten crumb. It’s a mistake I shan’t be eager to repeat. But . . . now there are fava beans and small lumps of bread lurking in odd places, hidden in drawers, tucked into the corners of shelves, taunting me any time I try to clean. There really must be something blessed about the bread because it never seems to mold. It just gets really, really stale. I suppose these little objects ought to remind me to give thanks for God’s bounty and to ask for St. Joseph’s intercession, but they don’t. They only make me wonder why I have to keep fava beans and bread crumbs all over my house.

I guess I haven’t been Sicilian long enough yet.

The take home loot: bread, beans, salt, and a rosary in Italian colors. The cookies had already been eaten.

We are strange creatures, we humans, who cling devotedly to our weird little habits that never seem weird until we see them through the eyes of someone who doesn’t share them. My husband feels about egg boxing pretty much the same way I feel about cluttering up the house with fava beans. Yet our weird little habits keep us rooted in the human family, reminding us that we belong to a community—and in the case of a St. Joseph Altar, that community is not only Sicily or the Church but the community of the saints in heaven. I suppose that’s worth the inconvenience of a few bread crumbs.

Especially when they come with cookies.

(I took these photos at the Cypress Springs Mercedarian Prayer Center in Baton Rouge, where the sisters are still trying to recover from the flood. They wouldn’t mind a little Lenten almsgiving, if you’re able.)

Karen Ullo is the author of the vampire saga Jennifer the Damned. To find out more, go to www.karenullo.com.

Alas, no satisfaction cans’t I receive

Update 4/24/17: I won! Will wonders never cease?

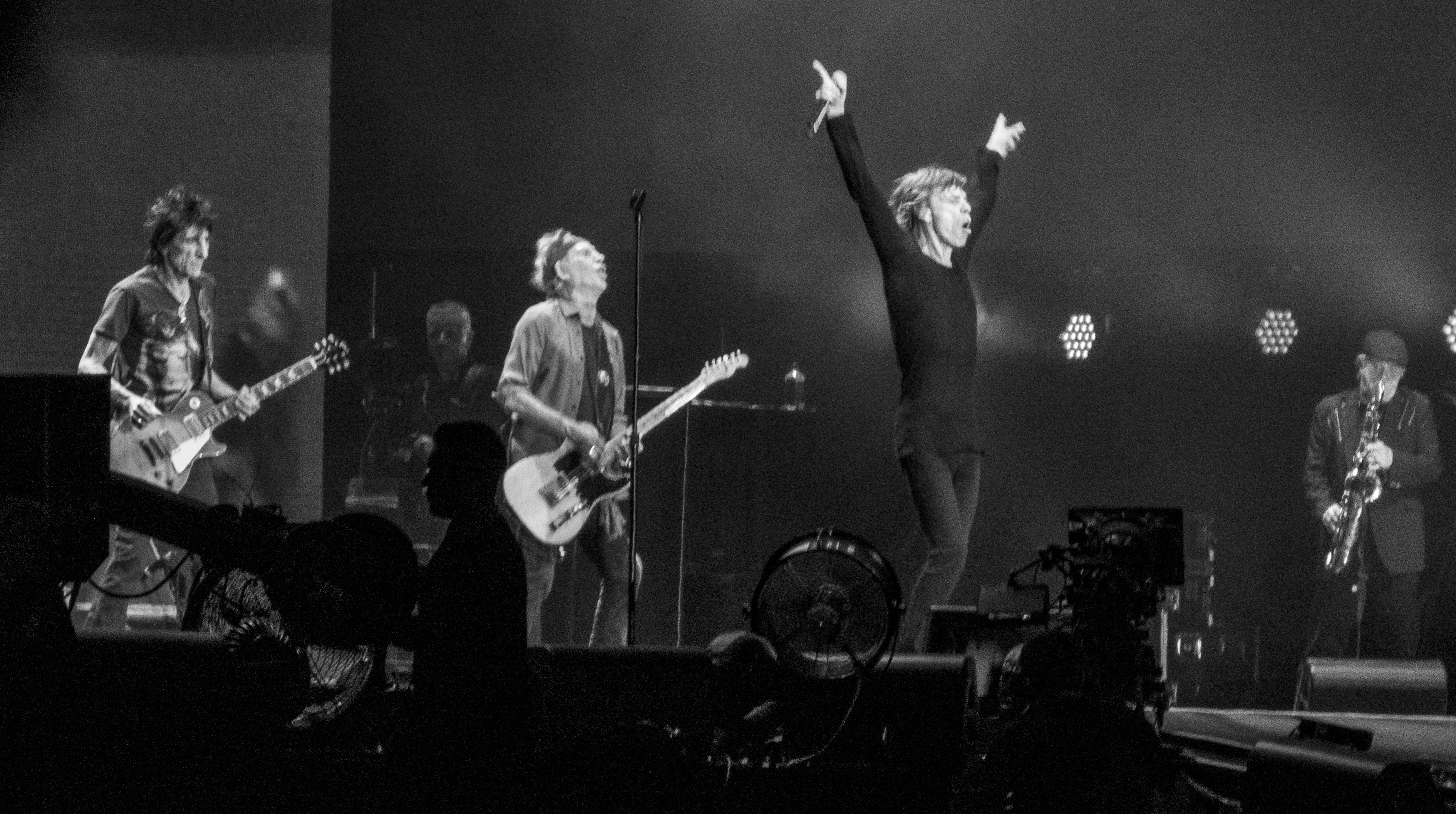

Last night, I happened upon this contest from Korrektiv Press to turn a pop song into a sonnet. I’ve had way too much fun writing this, so I thought I’d share and invite you to join in! Feel free to post your own creations in the comments here, as well as in the official contest.

Alas, no satisfaction cans’t I receive

Though the attempt repeatedly I make

Whilst rambling in horseless carriage, without reprieve

Some gentleman drones counsel I shan’t take

Say I, I cannot find contentedness

Though heartily do I endeavor more

The flashing box promotes dementedness

Of a launderer whose tobacco I abhor

Again, bereft, unsatisfied, I cry

Whilst I bemoan the maid with eyes so fair

Who to answer my entreaty doth deny

Even a fleeting glance with me to share

Cheerfulness eludeth me ever

In delight I shall indulge myself never

-The Rolling Stones

I Can’t Get No Satisfaction

Karen Ullo is the author of the vampire saga Jennifer the Damned. To find out more, go to www.karenullo.com.

Recent Comments