”Dost thou understand? I love thee!” he cried again. “What love!” said the unhappy girl with a shudder. He resumed,–“The love of a damned soul.” —Victor Hugo, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

I have gone on record many times (most recently here) to promote the particular genius of the horror genre as a tool through which Christians can confront the realities of evil and (when the genre is at its best) defy them through Christ’s love, either explicitly or implicitly. So, when I read the article “Now is a Perfect Time for Catholic Horror” by Stephen Wingate, in which he calls for a revival of the Catholic horror novel as a means of confronting the recent abuse scandals, I naturally agreed that he was on to something. But until such time as modern writers are able to produce work that engages the “difficult literary interrogation between Catholicism and evil… [and] provides a necessary look into how the church has become the horror for some,” we would do well to remember that Victor Hugo already gave us such a novel. More and more, it seems to me that The Hunchback of Notre Dame is a book for our times.

It may seem spiritually dangerous to turn to a novel that was once listed on the Church’s Index of Forbidden Books to help make sense of the current scandal,* but if we’re going to speak honestly about written works that pose spiritual dangers for Catholics, the Philadelphia grand jury report would be near the top of the list. In a world where the faithful have already been scandalized by villain-priests, there is no way to protect our souls from characters like Archdeacon Claude Frollo. We have already met such men in the flesh. We have seen the horrific effects of secrecy and denial; and if we owe it to the real victims to bring priestly crimes to light, we also owe it ourselves to revisit the prophetic novel that sought to do the same nearly 200 years ago.

When Victor Hugo wrote The Hunchback of Notre Dame, he was not “anti-Catholic,” as so many critics like to call him. What Hugo believed shifted radically and often during the course of his life, but at the time he published Notre Dame, he had not yet begun dabbling in spiritualism, nor embraced the kind of secular rationalism that characterized his later years. The Hugo of 1831 still identified with the faith of his baptism, even if he had become critical of the ways in which he often saw the faith abused among the clergy. It’s a spiritual space that many Catholics today will find achingly familiar.

However, the state of Victor Hugo’s soul when he composed Notre Dame is not only unknowable, but also irrelevant to a discussion of the work itself. The story is so powerful that it has endured across centuries and been translated into nearly every language of the globe. And what is that story but the interplay of light and darkness, faith and doubt, love and betrayal, within and through the Church?

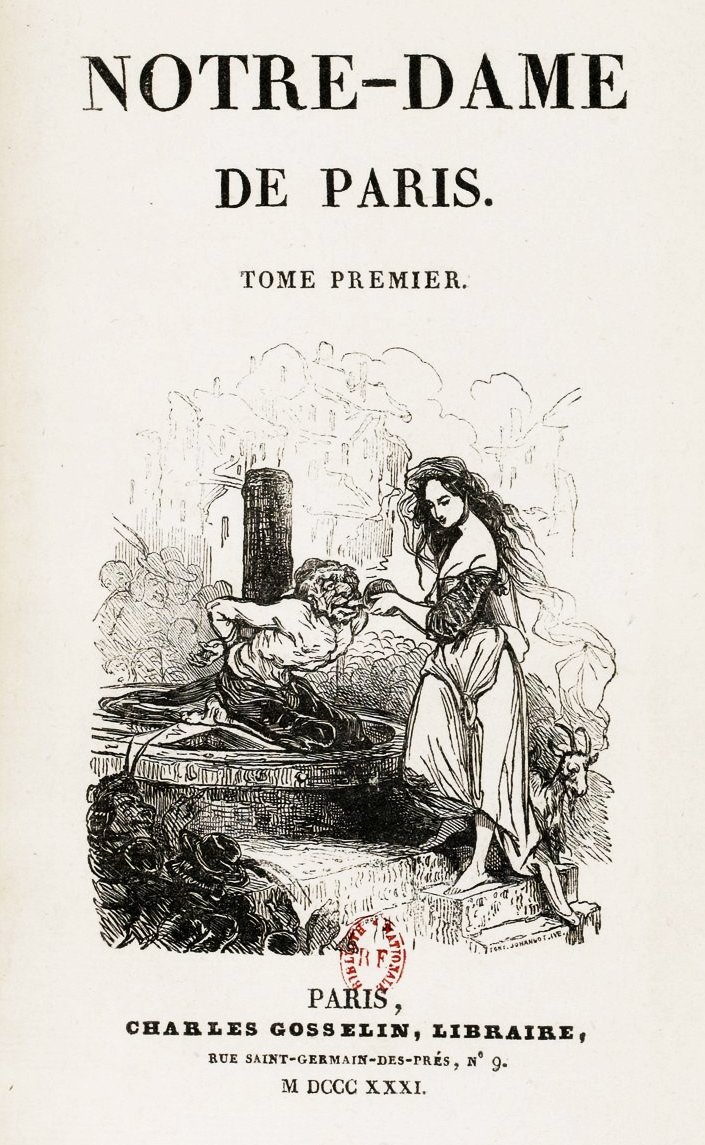

The original French title of the book is Notre-Dame de Paris; the cathedral is the title character and, arguably, the protagonist of the novel. The chapter titled “Notre-Dame” is devoted to the cathedral’s architecture, a song of praise to the building and a lament for the stupidities of man that, over the centuries, ruined certain aspects of its design. The cathedral is “a sort of human Creation, mighty and fertile as the Divine Creation, from which it seems to have borrowed the twofold character of variety and eternity.” This architectural depiction serves as a literalization of the church’s role in the novel; and not merely of the small-c church, Notre Dame, but also the capital-C Church, Catholicism. For Hugo, both are capable of bridging the gap between the temporal and the eternal, but man’s caprice has “brutally swept away” so much of what made them beautiful.

The original French title of the book is Notre-Dame de Paris; the cathedral is the title character and, arguably, the protagonist of the novel. The chapter titled “Notre-Dame” is devoted to the cathedral’s architecture, a song of praise to the building and a lament for the stupidities of man that, over the centuries, ruined certain aspects of its design. The cathedral is “a sort of human Creation, mighty and fertile as the Divine Creation, from which it seems to have borrowed the twofold character of variety and eternity.” This architectural depiction serves as a literalization of the church’s role in the novel; and not merely of the small-c church, Notre Dame, but also the capital-C Church, Catholicism. For Hugo, both are capable of bridging the gap between the temporal and the eternal, but man’s caprice has “brutally swept away” so much of what made them beautiful.

In the fifteenth century world of the story, the church still has most—but not all—of its grandeur intact. On the morning when the deformed child who will become known as Quasimodo is discovered in the porch of the church, Hugo is careful to tell us that this porch used to house statues of St. Christopher and Antoine des Essarts, a saint and a sinner, which had both been thrown down some fifty years before. Both saints and sinners have already become targets in the slow degradation of the Holy.

Yet the church is still intact enough to provide refuge for outcasts. The monstrous child exposed on the bed for foundling children is reviled by all the “good” Christians, but the young priest, Claude Frollo, chooses to adopt him. It is an act of true charity performed by a young man who has already taken on the guardianship of his baby brother after the death of their parents. This young Frollo is a rising star of the Church and a brilliant scholar. He names the foundling Quasimodo, which means half-made, “either to commemorate the day on which he found him [Quasimodo Sunday], or to express the incomplete and scarcely finished state of the poor little creature.”

Quasimodo Sunday is another name for the Second Sunday of Easter. It is taken from the opening words of the Introit, or Entrance Chant: Quasi modo géniti infántes, rationábile, sine dolo lac concupíscite, ut in eo crescátis in salútem, allelúia. This is a paraphrase of 1 Peter 2:2, and in the current English translation of the Missal, it reads, Like newborn infants, you must long for the pure, spiritual milk, that in him you may grow to salvation, alleluia. This translation has lost the sense of “half-made,” that we are not merely infants but incomplete beings, who can only be made whole by receiving the “milk” of Christ. But Hugo understands the Latin well; for him, it is only the half-made “apology for a human being” who is able to accept the Church’s invitation.

[Quasimodo’s] cathedral was enough for him. It was peopled with marble figures of kings, saints and bishops who at least did not laugh in his face and looked at him with only tranquility and benevolence. The other statues, those of monsters and demons, had no hatred for him–he resembled them too closely for that. It was rather the rest of mankind that they jeered at. The saints were his friends and blessed him; the monsters were his friends and kept watch over him. He would sometimes spend whole hours crouched before one of the statues in solitary conversation with it. If anyone came upon him then he would run away like a lover surprised during a serenade.

As long as he remains within the church, Quasimodo is happy. Yet the part of the church that makes him happiest—the bells which he is assigned to ring—also make him deaf. “Thus the only gate which nature had left wide open between him and the world was suddenly closed, and for ever. In closing, it shut out the only ray of light and joy that still reached his soul, which was now wrapped in profound darkness.”

It seems to me that Hugo isn’t quite consistent here. By making him deaf and closing the gate to the world, the cathedral has prevented Quasimodo from ever again being subject to the world’s scorn, or at least from hearing it voiced. He becomes even further encased in the church that has been “his egg, his nest, his home, his country, the universe.” Hugo wants to have it both ways: Quasimodo’s joy is both in the church and in the world to which the gate is now closed. But he is not clear about what light Quasimodo ever received from the world; the hunchback experiences nothing but abuse every time he leaves the church.

For Quasimodo, the cathedral fulfills Christ’s promise: Come to me, all you labor and are burdened, and I will give you rest. Father Frollo—who baptizes him, teaches him to speak, and gives him a purpose in life as the cathedral’s chief bell-ringer—serves the genuine role of a father. If the story had ended before either of these men ever laid eyes on Esmeralda, it might have been a happy tale.

In the years since he adopted Quasimodo, Claude Frollo has turned his scholarly pursuits away from theology first toward true science, then toward alchemy and sorcery. Rather than pursuing the Truth of God, he has idolized human knowledge, twisting the virtue of his keen intellect into a vice. The Claude Frollo who meets Esmeralda is a very different man from the one who first met the helpless child Quasimodo.

Esmeralda is a young gypsy dancer, physically as unlike Quasimodo as it is possible to be: lithe, beautiful, entrancing. Yet, like the hunchback, she is a lost child in need of a parent, a lost soul in need of succor. Esmeralda was stolen from her cradle to be raised among heathen strangers. But this time, Father Frollo cannot love the outcast enough to bring her into the church’s grace. Esmeralda stirs in him the same impulse toward love that Quasimodo did, but Frollo is no longer capable of anything but “the love of a damned soul.” He seeks not to shelter, but to possess; not to give, but to take. The Father has become an inversion of himself: no longer one who gives life, but one who takes it. Frollo is even able to acknowledge these changes:

And when, while thus diving into his soul, he saw how large a space nature had there prepared for the passions… he perceived, with the cold indifference of a physician examining a patient, that this hatred and this malignity were but vitiated love; that love, the source of every virtue in man, was transformed into horrid things in the heart of a priest, and that one so constituted as he in making himself a priest made himself a demon.

Frollo believes what we in the 21st century will recognize as a common argument: that the Church’s insistence on clerical celibacy, the denial of natural passions, is the root cause, or at least one of the root causes, of clerical sexual abuse. Frollo believes this argument, but his story does not illustrate its truth.** Lust is hardly Frollo’s only, or even his primary, vice. He does not chase after every skirt he sees, nor are his sins primarily driven by the desire for physical gratification. Rather, Frollo punishes his body, often working without food or sleep toward his goal of transmuting matter into gold. Frollo’s sin is the same as Adam and Eve’s: he covets knowledge that will make him godlike. His desire for Esmeralda has less to do with sex than with possession, because she—like transmuted gold, or Eden’s apple—is beautiful, forbidden, and unattainable.

When Esmeralda rejects his advances, Frollo destroys what he cannot possess. He turns her over to be hanged for a crime she did not commit. But Quasimodo has learned well from his father, and he follows the example of the younger, better Frollo; he adopts the orphaned child. In the novel’s most iconic scene, he snatches Esmeralda from the gallows and gives her sanctuary in the cathedral.

[He clasped] her closely in his arms, against his angular bosom, as his treasure, his all, as the mother of that girl would herself have done… at that moment Quasimodo was really beautiful. Yes, he was beautiful—he, that orphan, that foundling, that outcast; he felt himself august and strong; he looked in the face of that society from which he was banished… the human justice from which he had snatched its victim; those judges, those executioners, all that force of the King’s, which he, the meanest of the mean, had foiled with the force of God!

But the image of the triumphant outcasts wrapped in the consoling mantle of the church is not to last. The church is still Claude Frollo’s domain. He is the first to assault Esmeralda’s sanctuary, and Quasimodo cannot bring himself to kill his father in her defense; Esmeralda must wave a blade at Frollo herself. Her gypsy friends come next in an attempt to save her, which Quasimodo mistakenly foils because he cannot hear them speak their intentions. Then the King orders the sanctuary violated for the sake of ridding his kingdom of the supposed “sorceress.” The church’s ability to protect the powerless proves to be fleeting. As the king’s army closes in, Frollo alone has the power to save the girl, and he offers her a choice: life as his lover, or the gallows. Esmeralda replies, “I feel less horror of that than of you.” She goes to her death rather than submit to his lust.

I can only imagine how many real victims might see themselves reflected in Esmeralda. How many came to the Church looking for refuge, only to have their pastors, bishops, or archbishops issue fresh attacks by ignoring or disbelieving their accusations? How many faithful Catholics have felt like Quasimodo, carrying our wounded brothers and sisters into the bosom of the church for protection, only to be scolded and threatened by the very men we looked upon as fathers? How many predatory priests have used their power to issue ultimatums as appalling as the one given by Frollo to Esmeralda?

Frollo is true to his threat. Esmeralda dies on the gallows. An enraged Quasimodo pushes Frollo out of the tower of the cathedral where the two of them have watched the execution, and though Frollo catches himself on a pipe, the hunchback refuses to save him. As for Quasimodo:

About a year and a half or two years after the events with which this story concludes, when search was made in the vault of Montfoucon… they found among all those hideous carcasses two skeletons, one of which held the other in its embrace. One of these skeletons, which was that of a woman, still had a few strips of a garment which had once been white, and around her neck was to be seen a string of adrezarach beads with a little silk bag ornamented with green glass, which was open and empty. These objects were of so little value that the executioner had probably not cared for them. The other, which held this one in a close embrace, was the skeleton of a man. It was noticed that his spinal column was crooked, his head seated on his shoulder blades, and that one leg was shorter than the other. Moreover, there was no fracture of the vertebrae at the nape of the neck, and it was evident that he had not been hanged. Hence, the man to whom it had belonged had come thither and had died there. When they tried to detach the skeleton which he held in his embrace, he fell to dust.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame is a difficult book for Catholics. It calls into clear relief the potential horrors of trusting a Church that is led by a man or men as corrupt as Claude Frollo. It is a lesson that we cannot afford to ignore, yet the book leaves us with very little hope. I choose to read the ending as an intimation that perhaps Quasimodo, Esmeralda, and Esmeralda’s mother (represented by the empty bag) have found union as a family after death, but it is also legitimate to read the ending as one of pure despair. According to the novel, a hopeless grave is the sentence the Church has imposed upon those who trusted her, whom she betrayed. I have no doubt there are many who believe it, and we ignore this conclusion at our peril.

Yet there is one element missing from the portrayal of the Church in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and it is the most important one of all. Jesus Christ is hardly mentioned, and certainly never active. If the cathedral itself is the protagonist, it is a very humanized cathedral. It has “borrowed the twofold character of variety and eternity,” but it remains “a human Creation.” It is endowed with characteristics of the divine, but not the Divine Presence Himself. Quasimodo communes with statues and bells, but he never receives the “pure spiritual milk” his feast day calls for. The true warning we ought to take from the book is not merely that sexually corrupt priests pose a significant danger to the faithful. We hardly need a novel to tell us that. The real tragedy of The Hunchback of Notre Dame is that Quasimodo places his faith in the Church as an institution, not in Christ, her head. No human institution—not even one established by God—can ever be worthy of such faith. Those stone saints whom Quasimodo befriended failed to do what all true saints do; they did not lead him to know and love the living Jesus. Quasimodo is, unwittingly, an idolater; the church is his god. If there is anything we Catholics must be clear about in the context of our current scandals, it is that we do not worship idols. We worship the One who suffers with and for us. It is Christ, not the clergy or the Church, who will save the Esmeraldas and the Quasimodos from their graves—and, in His mercy, He will reach out a hand to the Claude Frollos while they plummet, too.

* The Church removed The Hunchback of Notre Dame from the Index of Forbidden Books in 1959.

** I’m not convinced that Hugo believed Frollo’s argument that celibacy must, by its nature, corrupt the priest—or, if he believed it in 1831, he had certainly changed his mind by the time he wrote the unforgettable portrayal of Bishop Myriel in Les Misérables.

Karen Ullo is the author of two novels, Jennifer the Damned and Cinder Allia. She is also the managing editor of Dappled Things literary journal and a regular Meatless Friday chef for CatholicMom.com. She lives in Baton Rouge, LA with her husband and two young sons. Find out more at www.karenullo.com.

This piece is so good–perfect, in fact. Your comparisons speak loud and clear to today’s horrid, clergy scandals. Bravo!

Thank you, Kaye!