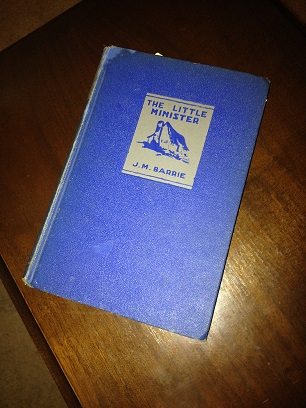

Everyone should make it a point, once in a while, to wander through a good used book shop and select a couple of titles he has never heard of before. I recently took just such a stroll, and I have found myself reading the way I used to when I was a kid: under the covers, completely absorbed, without a thought about what might be happening in the world outside the yellowed, dusty pages. Such was the spell cast by a smallish, blue hard cover volume, light-weight and without a dust jacket: The Little Minister by J.M. Barrie. I picked it up because I recognized J.M. Barrie, author of Peter Pan. I knew (because I have seen Finding Neverland) that he was a well-established writer before Peter Pan, but I had never heard of a single other one of his works. The little blue volume was frustratingly reticent about its contents. The publisher did not deign to print so much as a copyright date. There is nothing at all in the way of blurb or synopsis. When I bought it, I knew nothing about the book except that its author was famous for writing something else and that my particular volume had once belonged to Mary Louise Boone of Agnes Scott College. Not a single word gave me any insight about the story.

Everyone should make it a point, once in a while, to wander through a good used book shop and select a couple of titles he has never heard of before. I recently took just such a stroll, and I have found myself reading the way I used to when I was a kid: under the covers, completely absorbed, without a thought about what might be happening in the world outside the yellowed, dusty pages. Such was the spell cast by a smallish, blue hard cover volume, light-weight and without a dust jacket: The Little Minister by J.M. Barrie. I picked it up because I recognized J.M. Barrie, author of Peter Pan. I knew (because I have seen Finding Neverland) that he was a well-established writer before Peter Pan, but I had never heard of a single other one of his works. The little blue volume was frustratingly reticent about its contents. The publisher did not deign to print so much as a copyright date. There is nothing at all in the way of blurb or synopsis. When I bought it, I knew nothing about the book except that its author was famous for writing something else and that my particular volume had once belonged to Mary Louise Boone of Agnes Scott College. Not a single word gave me any insight about the story.

Lucky me. How often does anyone get the chance to embark upon a story without any preconceptions about where it will lead?

If you wish to leave off reading this review right now and dig up a copy of The Little Minister at your library to embark upon your own untainted journey, by all means do so. It’s a lovely little book. But if you must have something more to tempt you, then read on.

The Little Minister contains one potentially sizeable stumbling block for non-U.K. audiences, which is Barrie’s too-faithful rendering of Scotch accents. The book is set in a small Scottish weaving town called Thrums, and if I had not once had a friend from Airdrie, outside Glasgow, I might have given up trying to comprehend the characters’ gregarious prattle. Thankfully, I was able to play an imaginary recording of my friend’s voice in my head and persevere. It was worth the effort, because what unfolds in The Little Minister is as sweet a love story as I have ever read.

The title character is Gavin Dishart, a twenty-one-year-old newly-ordained “Auld Licht” (“Old Light”) minister who has come to take his first church (or kirk) in Thrums. The term “Auld Licht” means precisely nothing to this American cradle-Catholic, but I surmise that it refers to one of the more severe denominations of Scottish Protestantism. Gavin is wildly popular among his congregation, a rousing preacher, not afraid to beard lions in their dens by going out into the community to reproach its most obstinate sinners, which he does with some success. He is warned that the weavers of Thrums recently participated in a labor riot, and soldiers will inevitably return to exact punishment on them. The coming of the soldiers is heralded one night by an “Egyptian” woman (which is what the people of Thrums call a gypsy.) She rouses the weavers from their beds and warns them to mount a defense. Gavin bravely marches out to warn his people against violence and shame them into accepting the just deserts of their wrongdoing, which is how he first meets the Egyptian. Thus begins the telling of yet another star-crossed romance, this one between a straight-laced minister and a rabble-rousing gypsy.

The story is narrated by the dominie (schoolmaster) of nearby Glen Quharity, a stand-offish but not at all disinterested observer of Gavin’s story who offers many poignant insights about the nature of youth, infatuation, and love. The dominie knows a few things about love and love lost, things he learned from Gavin’s mother long ago.

Many things separate The Little Minister from other star-crossed romances, including Barrie’s inimitable style (if you’ve read Peter Pan, you will recognize his voice), the book’s unexpected ending (I will not tell you if it is comic or tragic, only that I was expecting one and found the other), and its distinctly un-modern understanding of love. Gavin and the Egyptian are subject to all the usual foibles of doe-eyed infatuation, including trying to deny that they are smitten. But they come to understand that love is a weighty thing, heavy with responsibility. The dominie is quick to remind both Gavin and the reader that any sacrifice made in pursuit of one love will come at the cost of many others. For Gavin to pursue marriage with the Egyptian will mean forfeiting not only his church, but also the security his mother enjoys from her son’s employment. The Egyptian, too, is tied by many connections that forbid the match even if she were willing to let Gavin sacrifice his livelihood, which she is not. One life is tangled up in many others, and to pull one thread too hard may unravel many more. And yet, who can ever help but pull the thread of love?

The Little Minister won me over because it is a lovely story, lovingly told. But more than that, it is a book about a true hero–a kind of book I have found to be all too scarce these days. “He was an obstinate minister, and love had led him in a dance, but in the hour of trial he had proved himself a man.” I would say, rather, he proved himself a man of God.

Karen Ullo is the author of Jennifer the Damned, now available from Wiseblood Books. Find out more at www.karenullo.com.

Recent Comments