The Warble

The Official Blog of Karen Ullo

Trying to Say ‘God’ Recap

It started with a miracle.

I mentioned recently that I was preparing to attend the Trying to Say ‘God’ conference about Catholic literature at Notre Dame. However, a few days before I was supposed to leave, Tropical Storm Cindy took aim at my airport in New Orleans. It was scheduled to make landfall right about the time I was scheduled to fly out. I sent an urgent prayer request to my fellow conference panelists and Dappled Things cohorts to ask Our Lady of Prompt Succor to let me come. She’s the patroness of Louisiana and protectress of our coasts. Then this happened:

That’s a screenshot of the radar on the morning of my flight. See that giant hole in the storm right over New Orleans? My plane took off on time and in sunshine.

I was predisposed to find grace at the conference, what with the Blessed Mother having opened the heavens to allow me to attend, and the people I met there lavished me with it. I think I laughed more in the course of those three days than I have in the past three years. Finally, I got to put not only faces but living, breathing humans to so many of the names I’ve interacted with in the writing world: the entire staff of Wiseblood Books, who published my debut novel; friends from the Catholic Writers Guild with whom I chat online weekly and even daily; and our own dear DT fiction editor, Natalie Morrill, to

Angela Cybulski of Wiseblood Books, me, and Natalie Morrill

name just a few. Of course, there were also many new names and faces added to the list of my dear friends, some of whom are so accomplished, it takes my breath away to think of myself as their “friend” (rather than their “gawking fangirl.”) And, because all things grace-filled are also loaded with weird coincidence, I ran into two former parishioners from my church, two beautiful and Christ-filled women whom it did my heart good to see again. If I hadn’t attended a single actual conference event, the trip would have been worth it just for the fellowship.

But of course, I did attend many of the panel discussions and keynote talks, including the one where I somehow got to count myself among the likes of Suzanne Wolfe, Angela Doll Carlson, Caroline Langston, and Kaye Park Hinckley, with Angela Cybulski moderating, as we discussed The Marian Effect: Building Strong Women in Writing and Life. Grace piled upon grace as those brilliant women allowed the Holy Spirit to speak through them. “Mother and artist are not career choices. They are states of being that are given to us.” -Suzanne Wolfe. “You become a part of the a story you want to tell people.” -Kaye Hinckley. I could have sat there all day. You can come help us keep the conversation going over at our new Facebook page set up by Angela Carlson.

Amazing women saying fabulous things

My favorite conference event actually had nothing to do with literature, but everything to do with “trying to say God.” The Notre Dame Vocale, a group of twelve singers with their conductor, presented a concert of Gregorian chant, Renaissance polyphony, and modern compositions based on both. It was forty-five minutes of pure bliss.

However, the big question for people who didn’t attend the conference is, of course, what did you observe? What is the state of Catholic literary culture? Who’s doing what, and is any of it working? For what it’s worth, from my limited one-person perspective, I observed first and foremost that the talent pool is deep and broad. Catholic writers are many, well-educated in both the craft of writing and the Faith, and unafraid to wear their Catholic identity on their sleeves. I also observed that Orthodox Christians—of whom I met several—are not only our brothers and sisters in Christ, but also very much our brothers and sisters in literary tradition and sacramental imagination. There were also a handful of people from other faiths, and a smaller handful who professed no faith but nevertheless found themselves curious enough to come. All were welcome, and good will reigned. How rare a gift that is.

However, it was also obvious to me that a good deal of ignorance and intransigence exist within the Catholic literary community. It’s ridiculous for a panelist to say, “No one publishes Catholic literary fiction,” when Joshua Hren, the founder of Wiseblood Books, is sitting in the room. It’s frustrating to hear Catholic publishers emphasize the cold reality of the bottom line without acknowledging room in their business models for the action of the Holy Spirit. It’s disheartening to hear that writers feel disconnected from, and not supported by, other Catholics when the Catholic Writers Guild, whose mission is to do just that, has a table set up in the next room. So much of the work we need to do moving forward is to divest ourselves of the fears and frustrations we have carried for too long, to come out of our introverted, writerly bubbles and simply help each other—and of course, one of the huge benefits of this kind of conference is to allow people to discover each other and do just that.

Finally, I’d like to say that this conference made it clear to me that the old cliché, “Beauty will save the world,” isn’t true. Beauty isn’t good enough; you must have love. Beauty can be cold, austere, and unforgiving, like an Antarctic landscape; love is always warm and transformative. Beauty can easily become an idol, a good sought for its own worth rather than as a pathway to God; love—when it is real, selfless, Christian love–cannot become an idol because God Himself is love. The speakers who sent their audiences out feeling that they had been nourished at a literary Eucharistic table were the ones whose messages overflowed with love: love for the subjects they spoke about; love for their craft as writers, editors, publishers, etc.; love for the work they produced; and most of all, love for the people they were addressing. As I’ve already said, the most valuable thing I took away from this conference was the fellowship of so many dear friends, old and new. The one thing I took away that actually matters is love. Heather King said in her keynote, “Love is our vocation,” and every ounce of her radiated the truth of her words. If all of us engaged in any aspect of a literary vocation can get love right, then we have already succeeded. For art to be truly Christian, its beauty must lead us to love.

Oh, and there was this bit of awesomeness, too:

Bro. Guy Consolmagno, director the Vatican Observatory; Johnathan Ryan of Sick Pilgrim; and renowned sci-fi author Tim Powers, sending everyone to Catholic Geek Heaven

You can find recordings of some of the conference sessions here.

Karen Ullo is the author of two novels, Jennifer the Damned and Cinder Allia. She is also a regular Meatless Friday chef for Catholicmom.com. She lives in Baton Rouge, LA with her husband and two young sons. Find out more at www.karenullo.com.

IS REAL LOVE A FAIRY TALE???

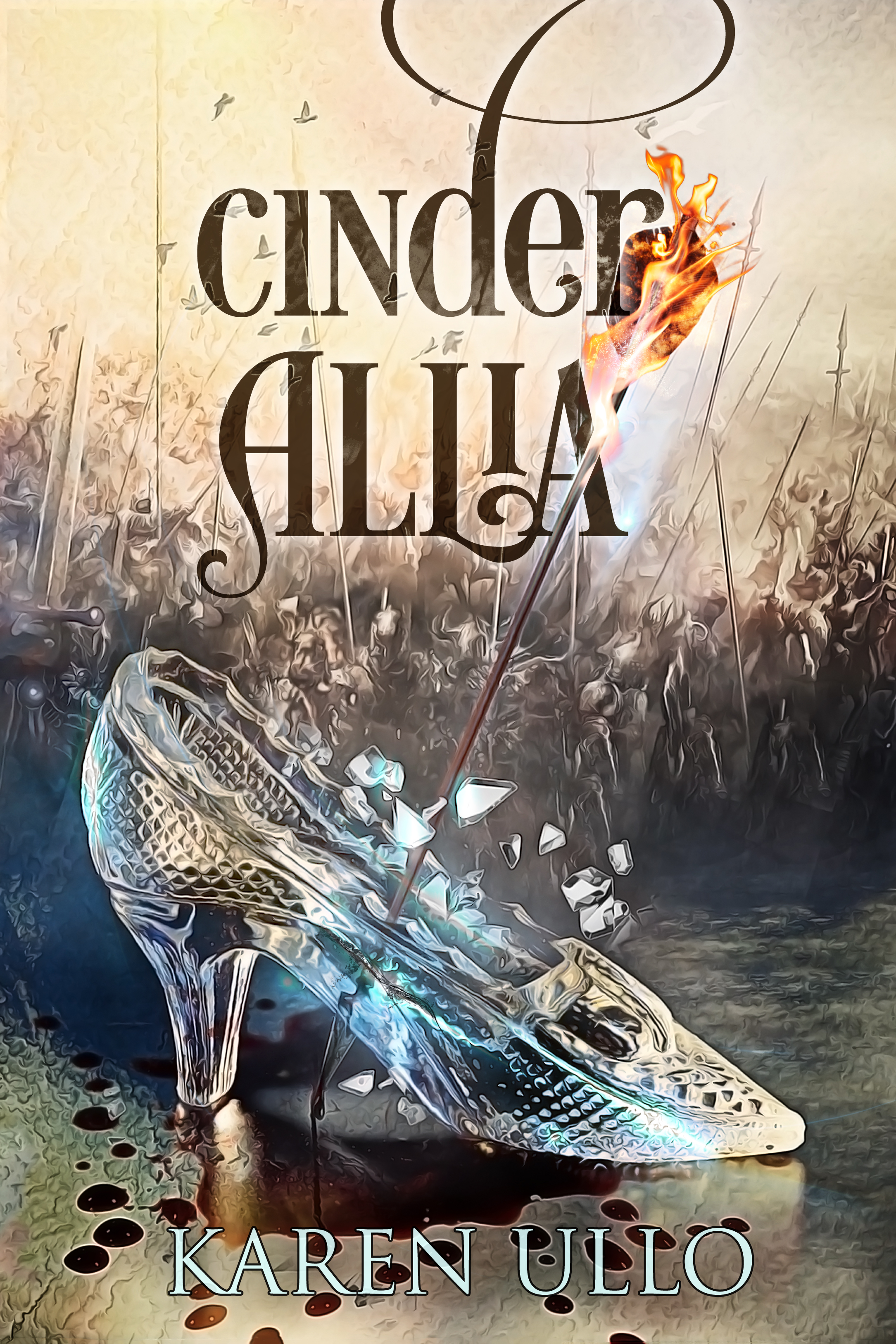

Early reviews for Cinder Allia are coming in!

Cinder Allia Coming July 6!

My new novel, Cinder Allia, will be released on July 6! Come join the launch party on Facebook that evening from 7:00-8:30 pm Central Time. I’ll post excerpts, we’ll geek out on all things Cinderella, and there will be opportunities to win great prizes including a free signed copy of the book! Hope to see you there!

“A corrupt, disintegrating kingdom is made whole by a young girl wielding the sword of justice in this engaging fairytale about the dire costs of both love and hate. Karen Ullo’s literary talent is captivating and thought-provoking, using symbolism and mystery to explore what keeps human beings in touch with the divine.” – Kaye Park Hinckley, author of A Hunger in the Heart and Birds of a Feather

Cinder Allia has spent eight years living under her stepmother’s brutal thumb, wrongly punished for having caused her mother’s death. She lives for the day when the prince will grant her justice; but her fairy godmother shatters her hope with the news that the prince has died in battle. Allia escapes in search of her own happy ending, but her journey draws her into the turbulent waters of war and politics in a kingdom where the prince’s death has left chaos and division.

Cinder Allia turns a traditional fairy tale upside down and weaves it into an epic filled with espionage, treason, magic, and romance. What happens when the damsel in distress must save not only herself, but her kingdom? What price is she willing to pay for justice? And can a woman who has lost her prince ever find true love?

Surrounded by a cast that includes gallant knights, turncoat revolutionaries, a crippled prince who lives in hiding, a priest who is also a spy, and the man whose love Allia longs for most—her father—Cinder Allia is an unforgettable story about hope, courage, and the healing power of pain.

Incarnating Words

Several months ago, Thomas Hanson asked on my post Literature, It Is a-Changing, “May I ask what you think musical study can offer to serious literary criticism? Or, maybe better put, what musical study can offer, that other studies can’t?” This isn’t exactly an answer, especially because I approach the question as a storyteller, not a critic. But I think this is as close as I will be able to come.

What is a word? We who have grown up in a literate society tend to think of it strictly as an intellectual tool, a signifier of ideas, an abstract symbol of concrete thought, but that is only one element of what a word truly is. A word is also an emotional trigger surrounded by context and laden with history; it is a physical experience of sound; and, when it is written, it is a physical experience of shape. Though we are largely unconscious of it, those physical and emotional experiences are intricately tied to our experience of the word. Shakespeare said a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, but I happen to agree with Anne Shirley (of Green Gables):

“I read in a book once that a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, but I’ve never been able to believe it. I don’t believe a rose WOULD be as nice if it was called a thistle or a skunk cabbage.”

She’s right: the phonetic and visual profiles of “skunk cabbage” are entirely different from those of “rose,” and human senses are inter-dependent. Change the aural and visual experience, and you change the entire sensory package. Likewise, words are emotional triggers, and there is little one can do to escape the associations of the word “skunk.”

As a singer, I have spent a good deal of time studying and practicing the physical experience of words, not only in English, but in languages I don’t actually speak like Italian, German, and Latin. All singing is by its nature storytelling, but it is storytelling that highlights the physical properties of words, using their tone, timbre, pitch, articulation, syllable stresses, tempo, etc. as elements of the tale itself. In fact, when I’m singing in a language I don’t understand, although it is essential for me to know the literal translation of the words, their physical properties become the only real tools I have with which to convey their meaning. Furthermore, singing joins words to the physical emotions of the human body, to facial expression and gesture. To me, the concept of the “word made flesh” is not some theological abstraction; it’s just what I do. I take words and give them flesh within my own body, and I attempt thereby to convey the fullness of their meaning— intellectual, emotional, and physical—to my listeners.

As Christians, we are called to experience the true Word made Flesh in even more depth, through even more senses, than the way I experience words as a singer. We are called to see and hear the Word in scripture, to study it with our intellect, to taste it and smell it in the Eucharist, to touch it and encounter it and become emotionally attached to it—that is, to Him, Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Word Incarnate—through our relationships with each other. It is the vocation of every Christian to bring this complex experience to others through the way we live: to bear the Word to the world through our flesh. But those of us who are called to the vocation of writing have another responsibility: to bear the Flesh to the world through our words.

To bear the Word in the vocation of a Christian storyteller, we must first immerse ourselves in the experience of Christ using the entirety of our being: mind, heart, and body. Then, we employ our talents to bring that same experience to life on the page, engaging the totality of the reader in stories that sing—directly or indirectly—of the Word Incarnate. We receive the Word in all of its depths and dimensions, and then we give it to others. A story that truly bears God to its readers reveals Him not only to the mind, but to the heart and the body as well. That is the particular genius of literature and its advantage over works of apologetics or theology: story has the power to speak to the totality of a human person. But in order for the story to do so, the author must first engage the totality of him/ herself in the writing.

Occasionally, young writers will ask me the best way to learn how to bring characters to life, and I tell them to take acting classes. Acting was a required part of my MFA writing program, so I am definitely not alone in thinking that it works. Like singing, acting requires the actor to involve his or her whole body in the process of storytelling, with a heavy emphasis on emotion and character motivation. These are things a fiction writer obviously needs to understand, but it’s also true that bringing words to life with one’s own flesh helps one learn how to put flesh into words. Acting is an immeasurably useful study for writers. Singing layers another dimension onto this dynamic of physical storytelling, requiring not only a different set of physical skills, but a greater adherence to structure, tempo, form, etc., all of which are useful elements in the creation of literature.

All singing is storytelling; likewise, all storytelling is by its nature musical. Story, even when it is written, is nevertheless a physical experience of sound, rhythm, tone, etc. As a storyteller, I consider it my duty not only to convey the literal meaning of the story, but to bring it to life through the words, paying attention to the physical effects of their sound and even shape, inviting the reader to an experience rich with taste, touch, smell, and emotion. As much as we humans like to think of ourselves as rational animals, the truth is that when our physical or emotional demands are at odds with our intellect, the physical and emotional demands usually win. In most circumstances, a hungry person is going to eat even if his mind says he’s already had enough; a sad person is going to cry, even if his mind says there is no good reason to do so. In the same way, a person who has been brought into contact with the beauty and mystery of God cannot help but feel it, even if his mind says there is no God to encounter. He is still likely to come back to feast on beauty again. Why else does our “post-Christian” society not tear down the great European cathedrals, nor ban Mozart’s Reqiuem from the stage? It is because these works incarnate at least a glimpse of the beauty of the Word; they engage our minds, our hearts, and our bodies in something Divine. It is this appreciation for the totality, especially the physicality, of artistic engagement that the study of music can afford to the study and practice of literature.

The one great advantage singers have over other musicians is the ability to engage the linguistic part of the human intellect at the same time we engage them in the aesthetics of the music: we can tell a literal story. Likewise, what music offers to storytelling, especially Christian storytelling, is the ability to transcend the intellectual power of words and wrap them in physical—that is, incarnational—beauty.

Karen Ullo is a writer, musician, wife, and mother of two small tornadoes–er, boys. Her novels are Jennifer the Damned (2015) and Cinder Allia (coming in 2017.) She is also a regular Meatless Friday chef for Catholicmom.com. Find out more at www.karenullo.com.

Recent Comments